Caltech Professor Bradford Cornell has written a great paper published in the Financial Analysts Journal called "Economic Growth and Equity Investing". He has performed a detailed, eloquent analysis that backs up my stock market valuation model (described here, updated many times here, and most recently conducted here). He posits that long-term, real earnings and dividend growth is unlikely to exceed 2% (I use 1.7% for the S&P 500 based on the historical trend). When combined with the dividend yield you are looking at a total real return of 4-5%.

Professor Cornell's paper is here: Download Economic Growth and Equity Investing I warn you, it is "wonky".

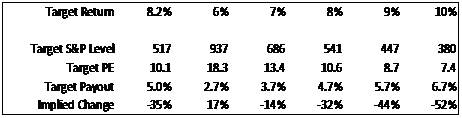

So if trend earnings growth is fixed, and the dividend yield is known at any given time, the variable in valuing the market is the assumption for future inflation. (Projected Return = dividend yield + real trend earnings growth rate + long term inflation rate.) Provided the long term inflation assumption is moderate, and thus interest rates are reasonably low, inflation and equity prices are positively correlated. I explain here how sensitive the market multiple is to changes in inflation expectations.

The key to beating the market short term is determining whether the market assumption for long-term inflation expectations is too low or too high. The rise in inflation expectations from 1.3% in March to 2.7% in January can explain virtually all of the rise in the stock market in that time.

I believe that investors should err on the side of assuming inflation will be lower than normal. I know this conflicts with what alot of people believe given our aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus. The problem is, that monetary and fiscal stimulus is just offsetting aggressive deleveraging in the private market, particularly among consumers and banks. Private deleveraging will continue until the housing market stabilizes and the banking system's leverage stabilizes. The banking system will not stabilize until after it has digested the proposed financial system reforms. Since the United States can not simply devalue its currency the way that smaller countries can, it can only deleverage via a period of belt-tightening. Deleveraging and belt-tightening mean struggling with deflation.

In my previous article "These are not Unprecedented Times" I discuss the long wave pattern called the Kondratiev Cycle. Google that term and you can learn all about it. While I don't think it can be used as a market-timing system and I realize that each cycle is different, the pattern it describes provides a good framework for understanding what is going on. Most economists have been building models with data that goes back to World War II and have left out a key part of the long cycle: the Kondratiev Winter. When the Autumn-season leverage-driven asset inflation has run its course, a long period of debt and asset deflation sets in. While stimulus may offset actual deflation, it will be difficult for inflation to be above average if the banking system is deleveraging and without a large currency devaluation. I'm not saying it's impossible. It's just highly unlikely.

The current market assumption for long-term inflation is 2.6%. That is slightly above the Fed's implied target of 2.0% to 2.5%. This with Federal deficits of 10+%, the Fed Funds rate of 0% and a large bout of "quantitative easing". The foot can not be on the stimulus pedal much harder than it is.

I don't make short-term market calls. Clearly, the stock market could continue to rise for a whole host of reasons. The next recession, whenever it comes, will likely be deflationary (no more bullets are in the stimulus gun) and the stock market will be hammered anew. Investors beware.