It has taken me a while to write the final installment of my 2009 Outlook series because of all of the wild uncertainty surrounding government policy and market movements. While much uncertainty remains, it is now somewhat clearer as to which direction policy will take.

To recap, in Part I, I gave the context of how our economic policy has been guided by the experience of the Great Depression, which leads us focus on supporting demand, particularly in housing.

In Part II, I described the link between our poor currency policy, trade deficits and the buildup in national indebtedness.

In Part III, I discussed the weak capital bases of the banks and how without the banks being shored up, the stimulus will not work.

The bank bailout program is fumbling slowly in the right direction, but will be ineffective until the housing market bottoms. The housing market remains strongly overvalued and will continue to fall well into next year at least. No realistic government program can stop the decline. Given the high levels of consumer indebtedness, largely tied to real estate, we should continue to expect consumers to increase their savings rates and curtail their borrowing for a long time to come. For the world economy, reducing its reliance on US consumers is an important structural shift that needs to take place. Unfortunately, however, it is a shift the world does not seem quite ready to make. The business sector would be in decent shape to invest were it not for the problems in the banking sector. Unfortunately, the combination of collapsing consumer spending and dried up credit is causing a wave of bankruptcies throughout the business sector.

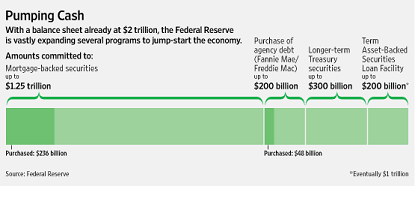

The only "savior" left is the government. The Fed is expanding the monetary base and Washington is running massive deficits. While this all seems inflationary, for the most part the government is fighting to offset the deflation in the private sector. It is not prudent to expect any sort of meaningful economic turnaround before the end of 2009. We could easily see the S&P fall to below 500 (it is at 670 now), and house prices fall another 20%. Cash and fixed income should be the investments of choice, with a small position in gold as a hedge against the possibility of a rapidly weakening dollar. Until we have reason to believe otherwise, we have to assume that the bust will return stock prices, house prices, and consumer and business indebtedness back to levels that prevailed in the early 1990s.

The Situation

The government is levering itself up in an effort to offset the decline in leverage among households and the financial sector.

Consumers

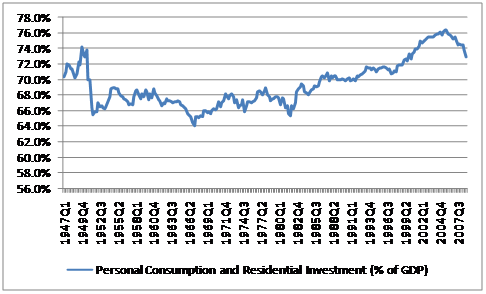

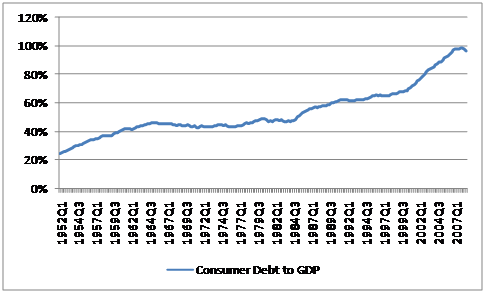

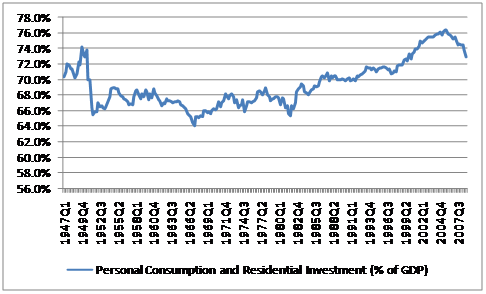

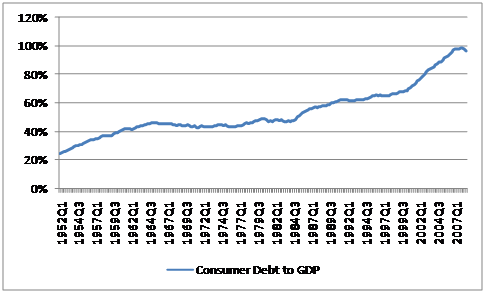

From the early 1950's to the early 1980's, personal consumption expenditures as a percent of GDP ran in the range of 62-63%. From 1982 to 2007, it climbed to 70%. Big surges came in the early 1980s and late 1990s, coincident with big stock market booms and high, disinflationary economic growth. These were also periods with a very strong and rising US dollar. Residential investment was strong in those times and in the late 1980s and mid 2000s Given the large supply/demand imbalance in housing, baby boomers needing to save for retirement, and the badly weakened financial sector, it would not be surprising to see the combination of residential investment and consumer spending to fall below the pre-1980s level of 68% of GDP in the next few years, a full 8 percentage points less than the peak level in 2005. We should also expect consumer debt to GDP to revert back to the early 1990s level of around 60%, a process that will probably take a decade or so.

Businesses

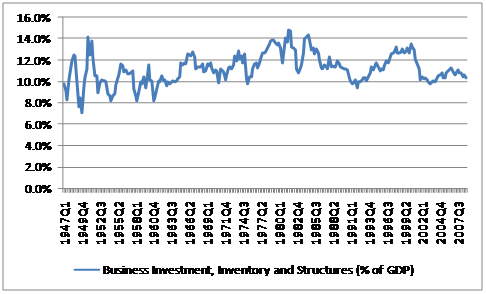

Business, on the other hand, is in reasonable shape.

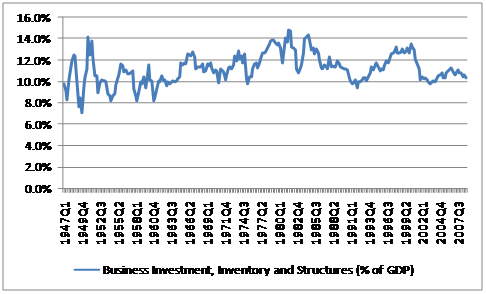

Business investment was relatively subdued this decade, following the large surge in investment in the 1990s, and profits were very high (until recently). While there was a surge in business indebtedness associated with the private equity boom, in general businesses were net savers this decade. As is typical in recessions, the next couple of years will likely see a wave of consolidation, bankruptcies and deleveraging among businesses while the financial sector contracts, after which business will be in a position to start investing again. We should probably expect business sector debt to GDP to fall from nearly 80% to under 60% over the next five years.

Interestingly, the decades with strong business investment and declining government outlays as a percent of GDP were the 1970s and 1990s, while the decades overseen by the business-friendly Republicans saw weak business investment and increased government outlays, mostly for the military. The pattern over the past four decades has been for there to be a tradeoff between business investment and defense spending on the one hand and between consumer spending and net exports on the other. Given the current upheaval in the economy and in economic policy, I'm not sure those relationships will continue to hold over the next decade.

Government

Over the next several years it is clear that, relative to GDP, government spending will rise, consumer spending will fall and business investment will be subdued.

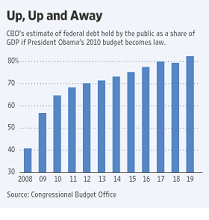

The Obama administration projects US budget deficits in excess of 10% of GDP for the next two years and around 5% of GDP for the next several years thereafter. These are massive figures unseen since World War II. It would not be surprising to see Federal debt to GDP rise to 70-80% of GDP by the end of Obama's first term. Such a rise could fully offset a decline in consumer debt to GDP back to early 1990s level of around 60% from the current 100%.

How government policy got us here

In US politics there are three schools of economic theory: Keynesians, "Supply Siders" and Monetarists. Since the Great Depression, all three schools have left their imprint on economic policy.

Fiscal policy: Keynesians vs. Supply-Siders

Booms and busts are caused by fluctuations in business investment, which get exaggerated by the expansion and contraction of the balance sheets of leveraged banks. Instead of focusing on the core of the problem, bank leverage, we have been hunting for a methodology to cure the symptoms of the problem, which are contractions in demand and debt deflation. Keynes advocated using government spending to offset periods of weak business investment, but he would have also advocated the government run surpluses when business investment was strong. Supply-siders advocated reducing taxes on investment and deregulating the business sector to encourage more business investment relative to government spending, which would increase productivity and lead to faster GDP growth. As was noted above, in the 1980s and 2000s, Republican administrations implemented a combination of Keynesian defense spending and investor-oriented tax cuts to offset weak business investment, while in the 1970s and 1990s, more liberal administrations cut defense spending and raised taxes during periods of strong business investment. In other words, the US electorate has actually successfully managed fiscal policy by changing the mix of Republicans and Democrats in Washington.

Monetary policy: the Monetarists and the dollar

Monetarists advocated increasing the money supply to offset the deflation caused by contracting bank balance sheets, and then withdrawing monetary stimulus when bank balance sheets were expanding. Contrary to popular belief, Fed Chairmen Volcker, Greenspan and Bernanke have actually practiced this fairly well. Prior to the late 1970s, however, monetary policy tended to be too loose. Since fiscal policy at the time tended to restrain business investment, the rapid money supply growth made its way into price inflation. The problem with US monetary policy has been that by focusing solely on US issues, the Fed has generally ignored the relative value of the dollar. As I outlined in Part II, periods of high real interest rates and falling nominal interest rates (like the early 1980s and late 1990s) lead to a strong US dollar, which leads to trade deficits.

The real estate money magnet

Because the government has put so much emphasis on homeownership and real estate tax incentives, the inflow of investment associated with the trade deficit has found its way into real estate lending. Add to the mix the mismanaged banking deregulations in the mid 1980s (with the S&L deregulation) and 2000s (when the GSEs and investment banks were allowed to expand their balance sheets) and the stage gets set for a banking crisis. Instead of incentivizing business investment during recessions, lower rates have encouraged consumer mortgage refinancing. The ability to manage consumer borrowing higher and higher has allowed for 25 years of economic growth, interrupted by only two brief recessions. The downside to this policy was the large buildup in US indebtedness associated with large trade deficits.

Unwinding the imbalance

The next 20 years could very well be dominated by the process of undoing this imbalance. Again, this is similar to what happened in Japan over the past 20 years after their bubble boom in the 1970s and 1980s. Japanese consumers borrowed large amount against their real estate holdings through the end of the 1980s and have since been retrenching. Real estate and stock prices in Japan have since retreated to the level of the early 1980s. The massive increase in fiscal stimulus in Japan in the 1990s (government debt to GDP rose to over 150% of GDP) and the extremely easy monetary policy of the 2000s only served to partially offset this deflation.

The US is almost certainly on the same path. Consumers' balance sheets are a mess, with crumbling asset values and high levels of debt tied to declining real estate. Consumers will now naturally focus on saving to repay debt and build up their assets for retirement, which is looming over the near-term horizon for baby boomers. Instead of giving lower-income consumers tax cuts to encourage spending, the long-term policy of the government should be focused on helping middle class consumers reduce their debt burdens and save. The United States will need to figure out a way to run trade surpluses to reduce its overall debt burden.

The operative assumption needs to be that the entire boom/bubble of the late 1990s will be wiped away. This means real estate and stock prices will go back at least to mid-1990s levels, and that the debt to GDP level will also return to those levels.

The Housing Problem

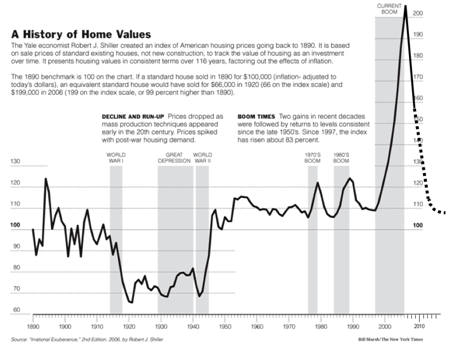

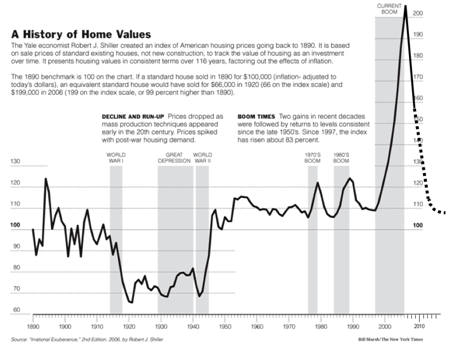

Here is an updated Case-Shiller chart of long-term real housing prices, courtesy of Barry Ritholtz. The level is currently at 158, 25-30% above the long term equilibrium. That would imply a bottom sometime in 2010-11 if prices continue down at the current pace. A return to equilibrium (or lower) is inevitable. We can slow the fall with government policy and end up with a long, slow deflation like Japan. The other way to cushion the flow is to inflate the currency, which is clearly what the Fed and Obama administration are trying to do.

The other glaring takeaway from this chart is that if you ignore the crazy run-up from 1997 to 2006, housing is not a good investment on an inflation-adjusted basis. From 1900 to 1996, the house price index rose from 100 to 110, an increase of 0.1% per year. The only reason that housing has appeared to be a good investment is that inflation has consistently surprised to the upside relative to mortgage rates, making housing a decent inflation hedge. It can also be a decent investment in markets that have done well, like coastal California, whereas it can be a poor investment in markets that have not, like Detroit. Otherwise, as a whole, the value of the nation's real estate has basically matched inflation and little more.

So do I think Obama's plan to "stabilize" housing prices will work? I do not. The decline in house prices is a freight train that would take trillions of dollars to stop. Until the housing market bottoms, probably not until sometime in late 2010 or 2011, we will continue to have uncertainty surrounding the value of assets on bank balance sheets. While there is uncertainty on bank balance sheets, there will continue to be an underlying deflationary tug on the economy.

The Stimulus

The purpose of the just-passed stimulus is to offset some of the collapse in consumer demand and business investment caused by the banking crisis. I do not believe that there is a short-term GDP "multiplier" greater than one on this spending. Spending focused on investment, like the broadband expansion, the electronic health record investment, transportation investment, government building weatherization, school construction and the electrical grid investment, are worthwhile in that they should increase long-run productivity, encourage private co-investment and can sop up excess construction workers and industrial capacity. Besides, since the government can currently borrow at interest rates of 0-3%, you don't need a massive ROI to justify the investment.

I would have preferred to see the aid to the states structured as loans that could be called in when economic growth returns. State and local governments have structured their budgets during the unsustainable boom times of the past 25 years and they should not be encouraged to maintain those levels of spending. Particularly egregious are the retirement benefits that have been promised to public sector workers. Expect revolts across the country as taxpayers rise up to rein in these benefits.

The Bank Rescue

As I outlined in my outlook Part III, I think the banking sector needs a lot more money to stay solvent. The Obama administration is on the right track with their stress tests and the $750 million contingency it has placed in its budget. The question is whether Congress will go along. I expect Obama will follow up with an overhaul of banking regulations that will focus on restraining balance sheet leverage. (The BIS standards are also moving in this direction.) I also expect there to be a great deal of political pressure for the US to re-privatize its bank investments within the next five years. These two factors will restrain both lending, as banks build up their capital bases, and money supply growth as TARP money flows back into the Treasury. It's the right thing to do, but will restrain economic growth.

The Obama budget

Without getting in to the merits of basic Democratic policies over Republican ones, I will focus on the items that will directly affect economic growth. Taxing high incomes more and providing rebates to lower income workers will marginally stimulate consumer spending at the expense of saving. On the other hand, the cap-and-trade carbon tax system will function as a consumption tax. Raising the tax rate on capital gains and dividends from 15% to 20% will make stocks marginally less attractive than bonds. The idea of the universal savings accounts, automatic 401k enrollment and government matching funds is a sound one and should help middle class families save more. The phase out of the mortgage interest deduction for high income earners should start to reduce the emphasis on housing investment and associated consumption by high earners.

The increase in consumption-related taxes and the idea of the universal savings accounts are pushing us in the right direction. The increased taxes on investors and small businesses are counter-productive, but Obama might get away with it because business investment is poised for a comeback next decade anyway. When the financial crisis eases, probably by early-mid 2010, there could be a brief surge in economic growth due to inventory restocking and pent-up investment demand. By 2011, however, it is currently projected that fiscal stimulus will ease, with the higher tax rates kicking in and the withdrawing of TARP funds from the banks.

The focus on education and health care are good for long term economic growth, but in the end the US already spends more per capita in these areas than other developed nations. The key in both of these areas will be on improving efficiency (aka productivity). Figuring out how to bring down the cost of health care would be a great boon to small businesses. The focus on energy and transportation could go a long way toward improving the US's terms of trade, but the focus on renewables at the exclusion of nuclear power is disingenuous at best. The most bang for the buck actually comes from increasing energy efficiency more than from alternative sources of energy.

As I described in this earlier post, it is now clear that Obama's budget blueprint is also a missile straight at the heart of the old Republican power structure. Health insurance companies, drug companies, student lenders, defense contractors, oil and gas companies, mining companies and large agribusinesses all stand to lose a great deal if Obama's budget passes in its current form.

At some point in the next several years we will need to figure out how to restrain the growth of Social Security and Medicare. It will become clear that economic growth will not be sufficient to produce an easy fix, and we will likely see a pretty major restructuring of these two programs, probably with an increase in the retirement age and reduced benefits for the wealthy.

As remote as it may seem right now, the big problem the US faces over the next two decades will be a shortage of labor. Economic growth (and supporting retirees) will depend on making each worker more productive. That means a policy mix focused on business investment, infrastructure investment, continuing education and health care. Overall, it seems that the Obama administration understands this, but is bogged down by some of the traditional anti-business Democratic Party policies.

Conclusion

While the second derivative of the economic decline is probably bottoming in this quarter or the next, we should expect economic growth in 2009 to remain negative throughout. Corporate profits in 2009 will be terrible. While my math puts the fair value of the S&P 500 in the range of 600, we could easily see a bottom in the 400-500 range if past bear markets are any guide.

By early-mid 2010, with housing prices nearing a bottom, the kicking in of the stimulus, a repair of bank balance sheets and inventory restocking, we might see a couple of quarters of decent growth. The problem will be that without strong global growth and a period of US trade surpluses, the growth will not be sustainable. Add to this the restrained growth of bank balance sheets and the specter of higher taxes, it will be difficult to maintain the rebound in growth. We could easily see a return to recession in 2011-2012.

Deflation will be the dominant economic impulse. While it seems like all of the money printing and the huge deficits should be inflationary, for the most part it will be offset by declines in indebtedness in the private economy. Until stocks are preposterously cheap, fixed income and cash should be the investments of choice. I'm not sure what the mix of a massive inflation in the monetary base and private market deflation mean for the price of gold. It is probably worth maintaining a position in gold as a hedge.

In the intermediate term, businesses should be poised for a strong investment cycle. We could therefore see a return to organic GDP growth by the middle of next decade. In any event, the US will not be able to sustain long-term GDP growth without a restructuring of world demand to support a long period of US trade surpluses and US debt reduction.

The scenario above is my base case. I will update it as circumstances change, as they almost certainly will.

![[Chart]](https://i0.wp.com/s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AO491_STIMUL_NS_20090128192101.gif)